A meme made its way around the feed this week — a simple split-screen: South Carolina stacked up against California, homicide rates, GDP, life expectancy, laid out like an accountant’s ledger for human order. California comes out ahead by every measure of safety and statistical prosperity. It gleams on paper: longer lives, higher incomes, lower crime. South Carolina, by comparison, looks ragged, poorer, less protected, more likely to bury its young before their time. Beneath that ledger sits the phrase that keeps echoing, half joke and half threat: “Don’t California my South Carolina.” It sounds like a cheap bumper sticker, but behind it is the oldest question any free people can ask themselves: would you rather live well-fed, longer, and safe in a well-built enclosure — or risk a shorter, harsher life for the chance to stay wild enough to matter?

A good zoo is not a trick. It works. It keeps its animals alive longer than they would ever last in the wild. It feeds them. It shelters them from predators. It surrounds them with enough illusions of freedom that the fence fades into the landscape. California, in many ways, is America’s best zoo. It has spent more than a century perfecting the art of curating risk. From the early Progressive reformers of the 1910s to the mid-century suburban dream and today’s modern blend of welfare safety nets, climate codes, and pilot programs for universal basic income, the promise is the same: no one needs to fear the darkness outside the fence. In return for that security, you accept a trade — fewer claws, fewer teeth, fewer chances to fail so completely that you become a threat to the others inside.

By contrast, places like South Carolina — and the broader cultural belt that includes states like Texas, Montana, and the Dakotas — remain shaped by an older impulse. These are regions where the edge of the forest still feels close, where life expectancy is lower, where violence is more common, where the bear gun or the revolver is not just a relic but a reminder that the fence is not inevitable. To live this way is to accept the possibility that life will be shorter, colder, less predictable — but also to believe there is something worth preserving in the raw freedom to stand alone when you must.

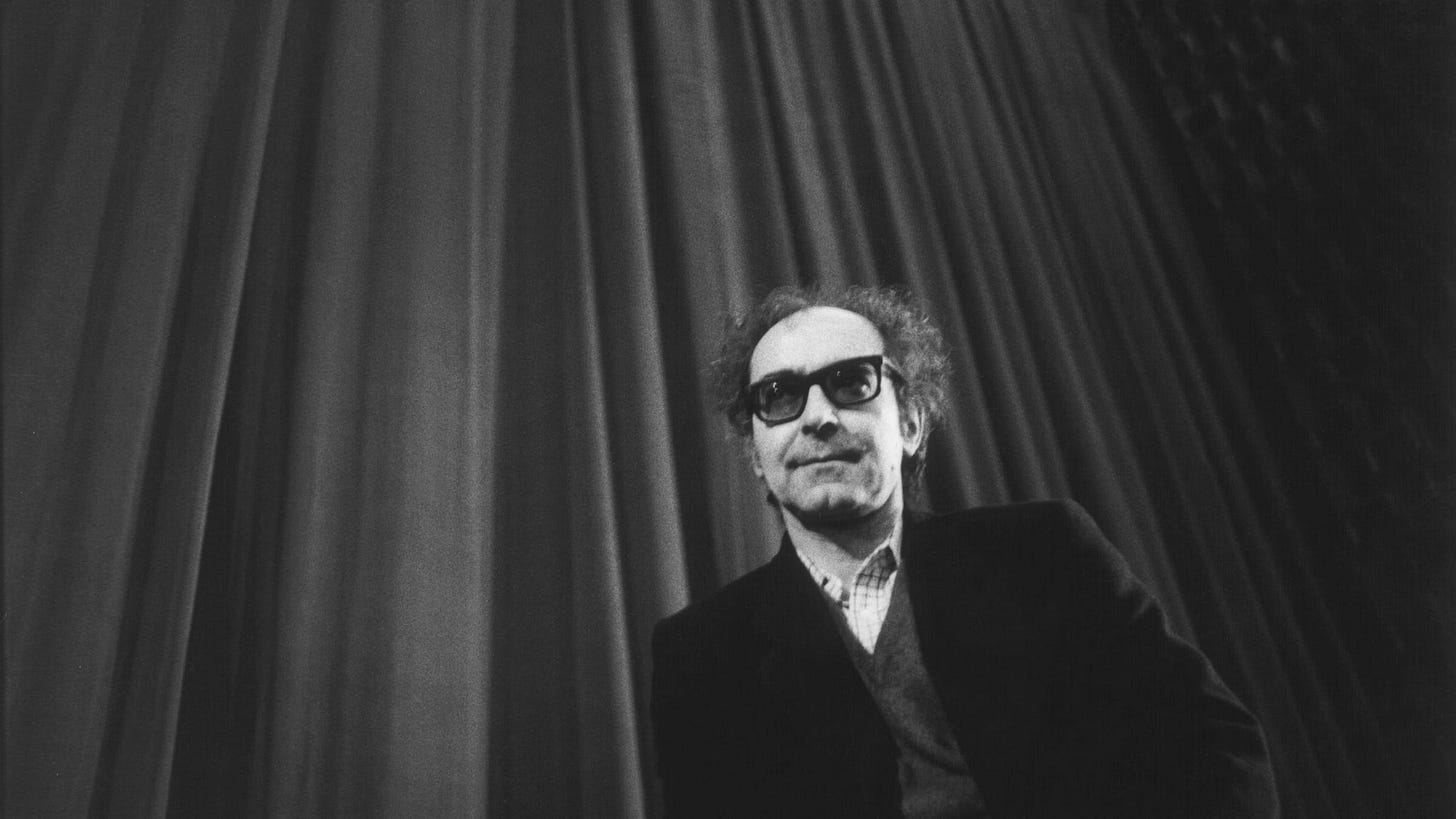

The French filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard understood this tension when he released Alphaville in 1965. At the height of France’s postwar technocratic boom, Godard imagined a city governed by Alpha 60, a sentient computer whose logic and order eliminate poetry, contradiction, and unpredictability. In Alphaville, citizens live behind locked doors and surveillance corridors, each one humming with a simple code: “occupé, occupé, libre.” These are not gates to real freedom but mechanical signs allocating interrogation rooms like cells in a perfect zoo. “Libre” means vacant, not free — a mocking binary where the machine’s promise of freedom is always conditional, always a dead end. True freedom must come from the wild mind that refuses the corridor altogether, carrying its claw, its revolver, its scraps of outlaw poetry back into the darkness beyond the fence.

Godard’s detective, Lemmy Caution, slips into this system from the “Outer Nations,” the places that still lie beyond the computer’s reach. He smuggles in a revolver and scraps of poetry the machine mind cannot parse. He is the reminder that no fence is perfect, that some animals will still claw at the door marked libre, that the price of comfort is always teeth. The film was Godard’s warning to his own country. Postwar France had emerged from the terror and hunger of the early twentieth century to build the Trente Glorieuses — thirty glorious years of prosperity, modernization, and the dream of rational planning. But the generation that raised the barricades in 1789 knew the danger too: a zoo, no matter how gentle its keepers, is still a cage if you lose the memory of the woods outside.

It is no accident that France gave America the Statue of Liberty and not the Statue of Perfect Safety. They did not ship us an engraved promise of permanent care. They gave us a flame. The poem so many remember — “Give me your tired, your poor…” — is an American addition. The statue itself stands as a torch against the wind, a dare rather than a guarantee. Keep this flame if you can. Stay wild enough to need it.

America’s true inheritance was never the British garden walls or class hierarchy. It was the French instinct that freedom is a brutal wager. The first Puritans crossing into the New World feared the wilderness more than any native tribe they would ever meet. The forest was a moral abyss: no fences, no kings, no keepers, no hedge against failure. But out of that abyss grew the frontier mind, the rugged individualist who does not exist without risk. Emerson’s self-reliance, Turner’s frontier thesis, the Texas Ranger, the cattleman, the constitutional carry states that still draw a line in the dust and say: you may build a fence, but it will not hold if we decide to walk.

This tension appears in every cultural echo. The caged bird sings not because it is content, but because its song is the only thing the bars cannot reach. The madwoman in the attic is perfectly kept: well-fed, well-watched, safe from the cold — but never free to run into the woods that would probably kill her sooner than her padded cell. There are truths in feminism, literature, and American myth that all circle back to the same idea: the wilderness is not safe. That is exactly why it matters.

California’s better zoo is real. Its gates are soft enough that most who leave end up rebuilding them elsewhere. The irony of the bumper sticker is that those who say “Don’t California my South Carolina” often flee the zoo only to carry it with them — to Austin, to Boise, to Montana. The gate becomes a state line, then a city ordinance, then a homeowners’ association, then a culture that says: we would rather be safe, curated, well-fed. And one day, the corridor that hums occupé is all that remains.

The frontier mind knows this. Some people will die younger, hungrier, more violently. They will be measured and found wanting by any accountant’s ledger of safety and comfort. But they will keep the bear gun, the revolver, the door marked libre that you cannot lock no matter how strong the fence becomes.

When Godard filmed Alphaville, he gave us more than a dystopia. He showed how the guardians never really kill the spark. The animals do it themselves when they choose the warmth of the cage over the cold wind outside. The flame in the harbor stands for nothing if no one remembers what it means to stand under it without a keeper. Liberty, equality, and brotherhood belong to the wilderness, not the pen.

That is the choice. Live free or zoo.

📚 APPENDIX

Jean-Luc Godard (1930–2022)

Swiss-French filmmaker, one of the leading figures of the Nouvelle Vague (French New Wave). Famous for Breathless (1960), Contempt (1963), Alphaville (1965), and decades of radical cinema. Politically leftist, formally experimental, always critical of bourgeois comfort and conformity.

About Alphaville (1965)

A hybrid of science fiction and noir detective film. Lemmy Caution, an agent from the wild “Outer Nations,” enters a technocratic city ruled by Alpha 60 — a sentient computer that abolishes contradiction and poetry. The film explores surveillance, rationalized order, and the cost of killing the wild spark. Won the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival but never matched the populist impact of Breathless.

The Nouvelle Vague (French New Wave)

A loose movement of filmmakers in late 1950s and 60s France (Truffaut, Godard, Chabrol, Varda, Rivette, Resnais). Broke away from studio formalism, used handheld cameras, jump cuts, and fragmented narrative. Reacted against both American commercial cinema and France’s technocratic shift. Critiqued state power, mass media, and the industrial containment of life.

France in the 1960s: Modernization vs. Revolution

After WWII, France entered Les Trente Glorieuses — three decades of rapid economic growth and welfare expansion. But the nation also faced decolonization crises (Algerian War, Indochina) and youth revolts. Godard and his peers felt torn between the Enlightenment ideal of liberty and the temptation of total technocratic curation.

Puritan Fear of the Wilderness

Early American settlers feared the forest more than the king. The wilderness was a spiritual and physical void where their fragile moral order could dissolve. This fear seeded the mythos of the rugged individualist: the one who could survive outside the stockade walls without a keeper.

Rugged Individualism & “Live Free or Die”

A core American myth: Emerson’s self-reliance, Turner’s Frontier Thesis, the Texas Ranger and cowboy archetypes. “Live Free or Die” is the New Hampshire state motto — the spirit that freedom means risk, and safety bought with submission is not freedom at all.

The “Zoo” States vs. the “Free” States (A Crude Map)

Zoo States/Cities: High-trust, highly regulated, deeply social-democratic cultures: California, New York City, Seattle, Portland, Chicago (in theory). Dense, curated, protective.

Free States: Texas, South Carolina, Montana, Wyoming, much of the Mountain West and the rural South. Low-trust toward centralized authority. Constitutional carry. “Don’t Tread on Me.”

This is cultural, not strict geography — you’ll find free enclaves in blue states and curated enclaves in red states.

Private Prisons as Old Zoos, Welfare Cities as New Zoos

Worth noting: the crude prison industrial complex is the hard cage version. Modern “zoo” urban planning is the soft version: longer lifespans, more gentle curators, better toys, but still fences — often invisible.

Why “Alphaville” Still Matters

Godard’s cautionary tale reminds us: The guardians rarely kill freedom directly. We do it ourselves by loving the cage so much we forget the door is there. Lemmy Caution’s revolver and scraps of poetry are reminders: the wild spark will always cost you something.

The phrase "Live free or zoo" is a play on the motto "Live free or die," often associated with the state of New Hampshire. It's a humorous juxtaposition, implying a preference for freedom (represented by "live free") over confinement in a zoo (represented by "zoo"). The phrase isn't a formal saying or motto in any context.

tl;dr

The provided text, "Live Free or Zoo: America’s Alphaville Choice," critically examines the societal trade-off between personal liberty and perceived safety, using the contrasting examples of California and South Carolina. It presents California as a "zoo-like" society, offering security and longer lifespans at the cost of genuine freedom, while South Carolina embodies a riskier, yet more untamed, existence. Drawing parallels to Jean-Luc Godard's film Alphaville, the article suggests that an overemphasis on curated order can suppress individuality and the "wild spark" of humanity. Ultimately, the author posits that choosing comfort and security can lead to an unwitting self-imprisonment, challenging readers to consider whether the benefits of a "zoo" outweigh the inherent value of an unconstrained life.

Share this post