This episode took two attempts.

The first time I hit record, nothing landed. I wasn’t focused, the ideas weren’t cohering, and everything felt half-formed. The second time worked, not because I had better notes, but because I stopped trying to organize the thought and let it run where it wanted to go.

What I’m circling here isn’t a policy position or a moral argument. It’s a pattern. One I’ve seen enough times in enough places that I don’t think it’s accidental, and I don’t think it’s partisan either.

America is very good at building large systems. It is much worse at turning them off.

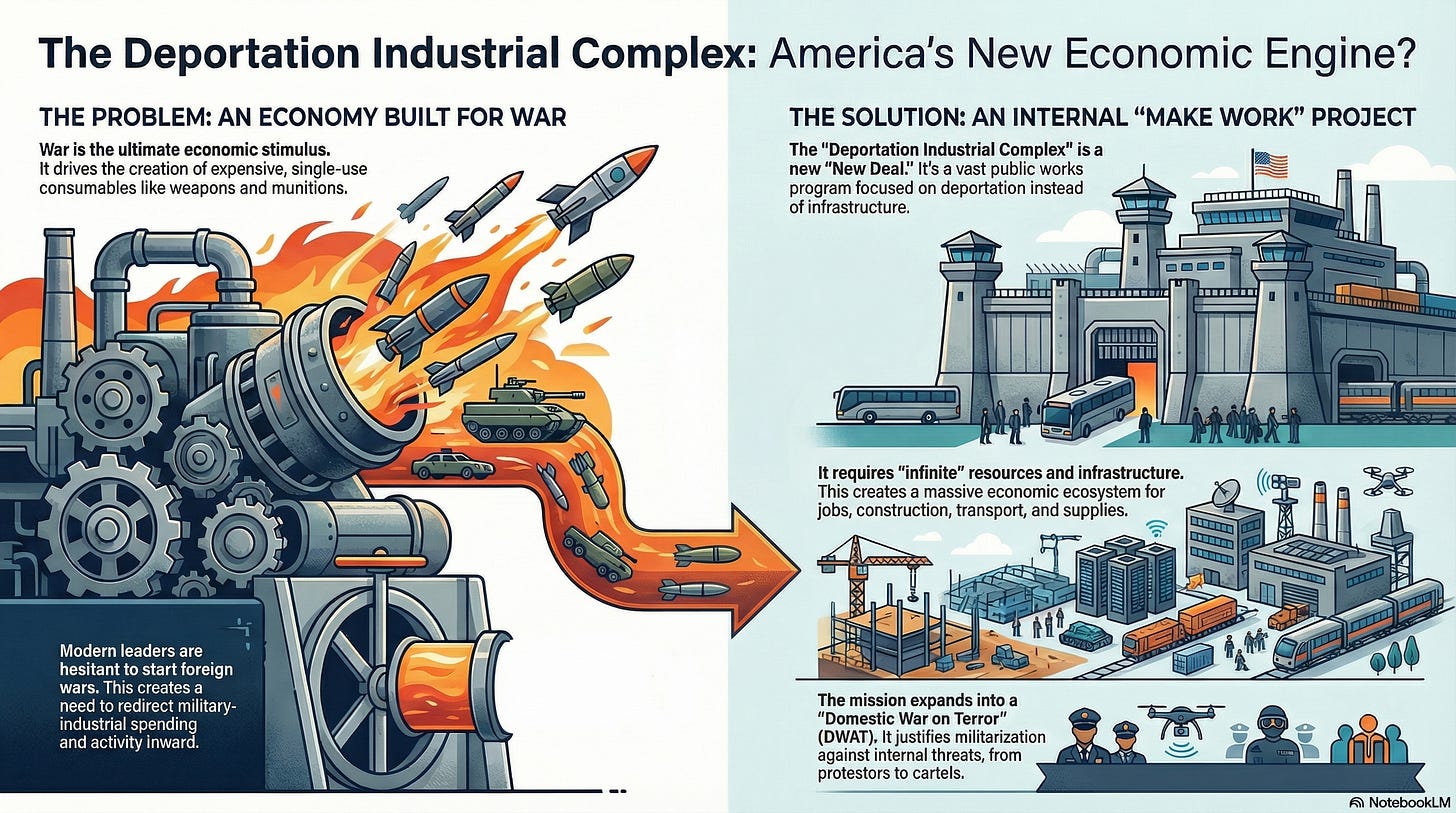

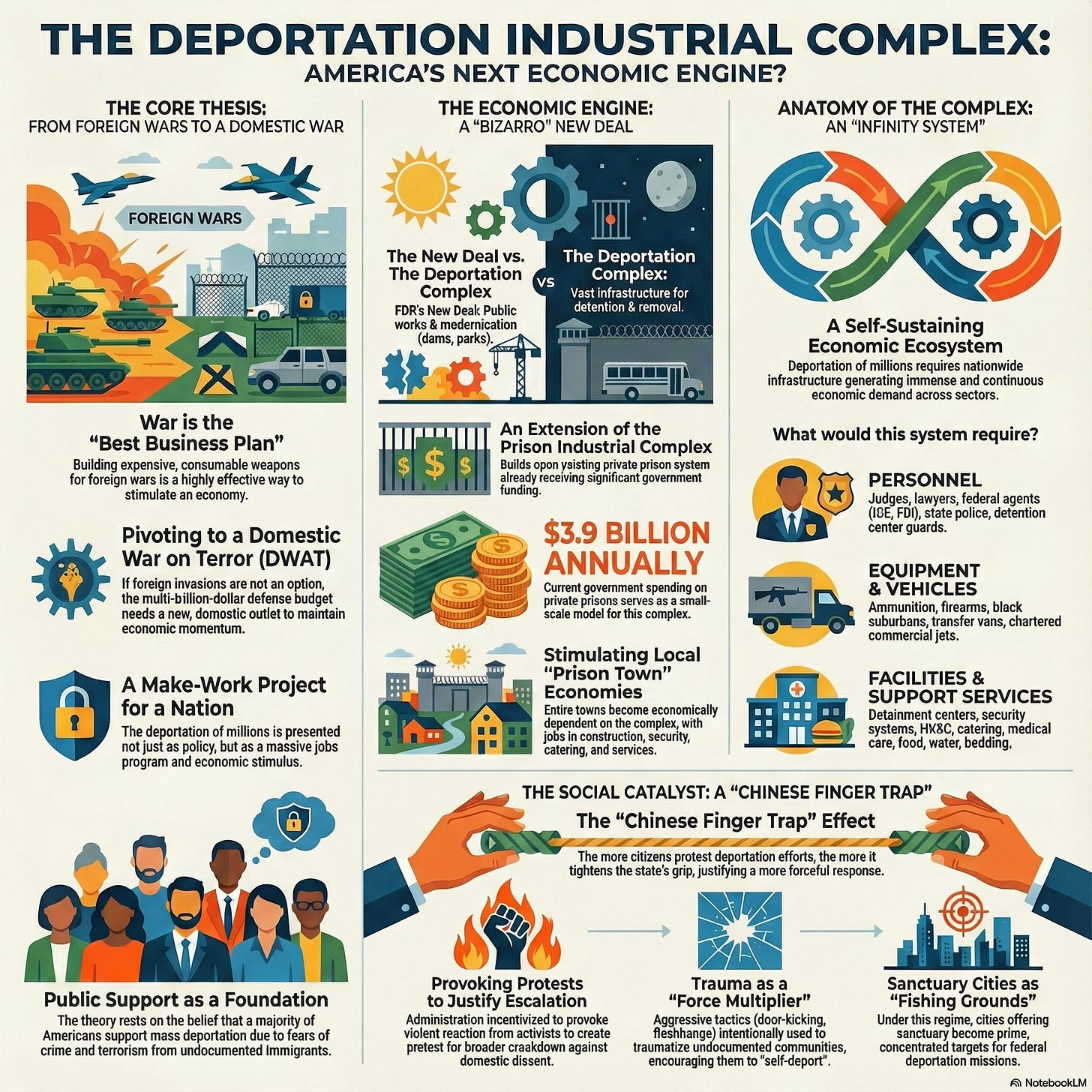

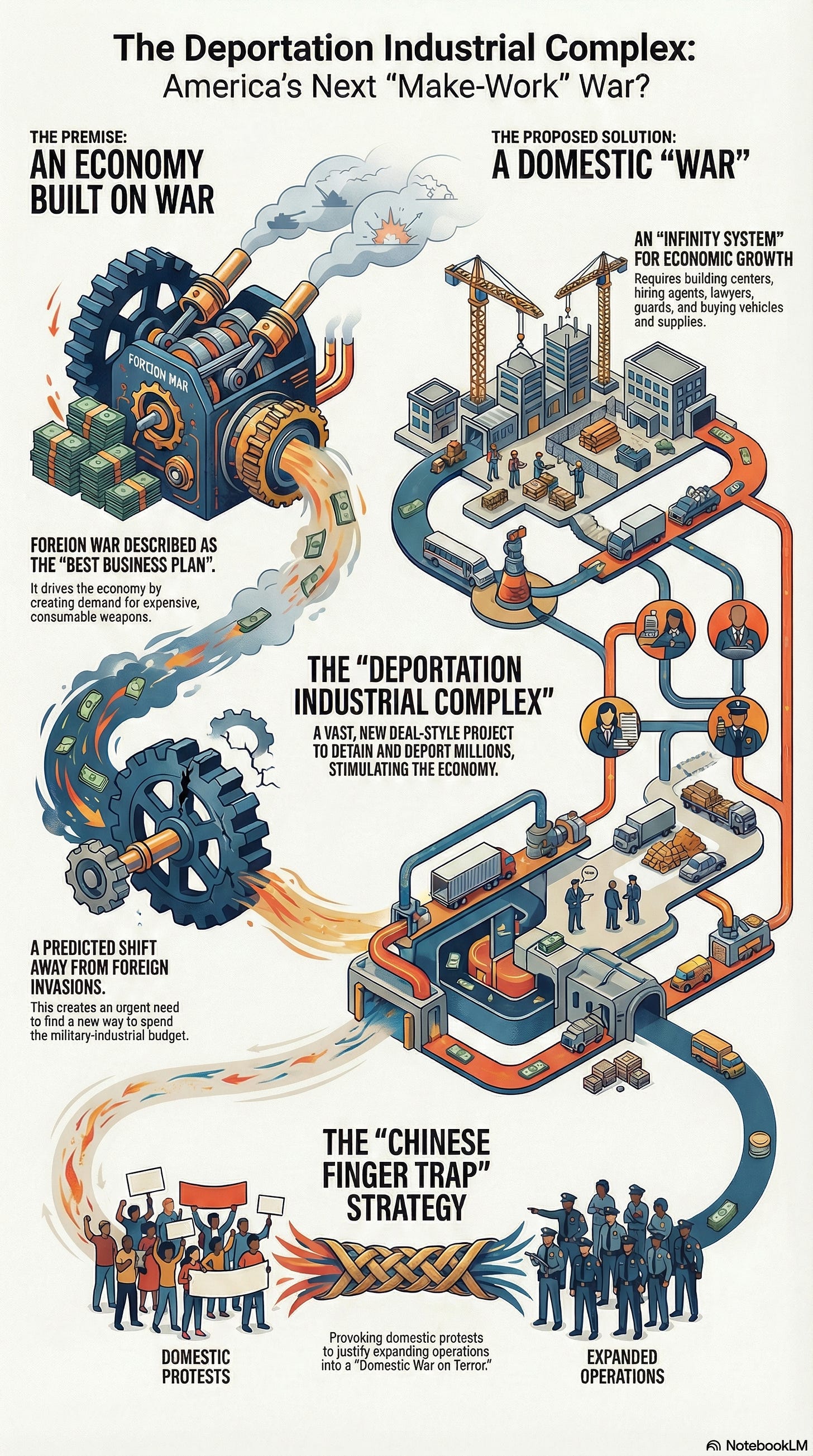

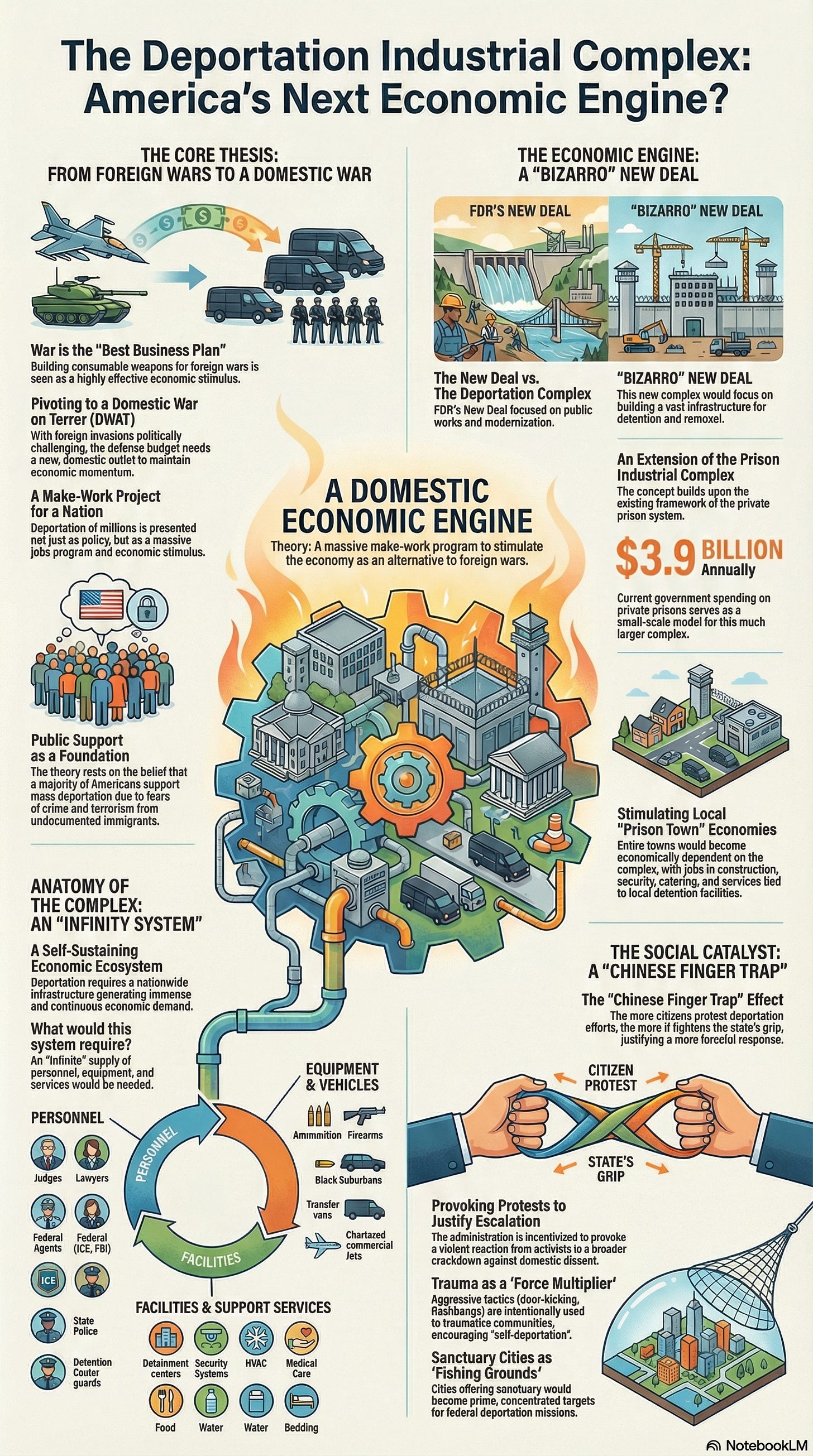

For most of the last century, war has been one of the primary ways the United States organized itself economically. Not just in the obvious sense of weapons and soldiers, but in everything that fans out from that. Manufacturing, logistics, contracting, transport, legal authority, emergency powers, entire regional economies. War isn’t just something America does. It’s something America uses to keep very large machines running.

The Global War on Terror was especially good at this. It lasted long enough to feel permanent. It normalized enormous budgets, standing authorities, and a constant sense of background emergency. It trained people, built careers, created firms, and locked in expectations about what “normal” federal spending looks like. For more than twenty years, there was always somewhere else the machinery could point itself.

But external wars don’t scale infinitely. At some point, the escalation risks get too high, the returns get too fuzzy, or the public just gets tired. When that happens, the systems don’t politely shrink. They look for somewhere else to go.

That’s the moment we’re in now.

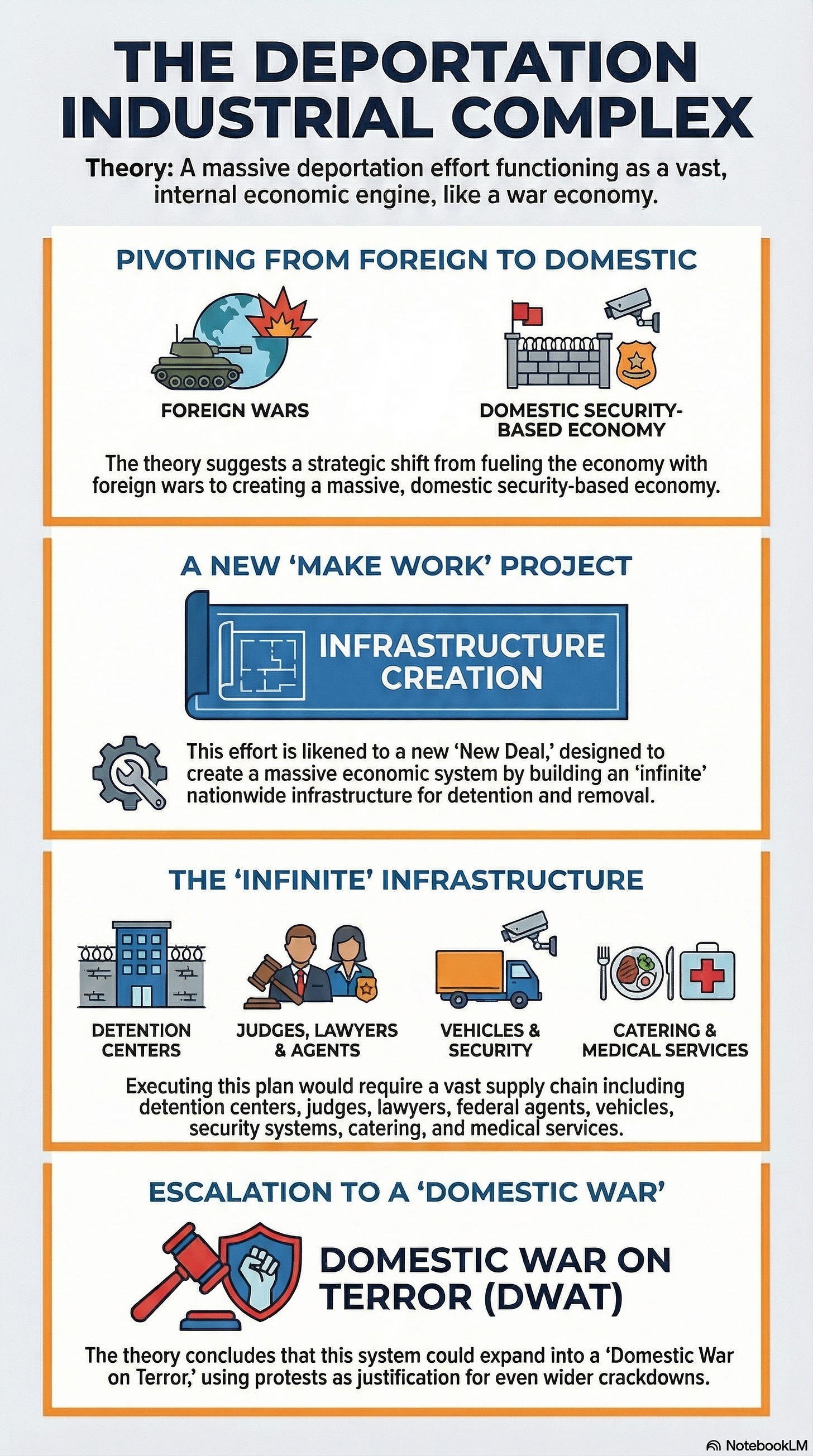

What’s interesting to me is not immigration as a moral issue, but immigration enforcement as a systems problem. If you strip away the rhetoric and just look at it mechanically, mass deportation is an enormous administrative project. It requires transportation, detention, staffing, courts, lawyers, guards, food, medical care, vehicles, aircraft, facilities, procurement, and coordination across federal, state, and local agencies. It looks, structurally, a lot like a national mobilization effort.

That’s not praise or condemnation. It’s just scale.

Once you see it that way, the idea of a “deportation industrial complex” stops sounding conspiratorial and starts sounding obvious. Any program that large will generate vendors, contractors, towns, careers, and political constituencies that depend on it continuing. We already know this from the prison system. We know it from defense contracting. We know it from every other large federal apparatus that started as a response to something and became a permanent feature of the landscape.

What changes, when enforcement moves inward, is the framing.

Externally, the organizing concept was terrorism. Once someone was categorized that way, the rules changed. Extraordinary measures became permissible. Distance no longer mattered. Normal legal friction could be bypassed. That logic didn’t disappear when the GWOT lost momentum. It just lost a clear external theater.

Domestically, you don’t need the exact same definition. You just need categories that carry risk. Undocumented migrants. Cartel affiliates. Extremist networks. Supporters. Facilitators. Protesters who interfere. Each category expands the administrative surface area a little more. Each expansion justifies more capacity, more funding, more permanence.

That’s what I mean when I say “DWOT.” Not that there’s a declared domestic war, and not that the tactics are identical, but that the logic has come home. The same organizing principles. The same emergency elasticity. The same assumption that once a system is built, it should be used.

There’s a temptation to think that protest or resistance will naturally slow this down. Sometimes it does. But just as often, it becomes part of the fuel. Visibility justifies response. Escalation justifies capacity. Capacity justifies permanence. This isn’t unique to any one movement or administration. It’s how large enforcement systems behave when they’re under pressure.

None of this requires evil intent. That’s the uncomfortable part. Systems don’t need villains to keep moving. They need momentum, incentives, and the absence of a compelling reason to stop.

Over time, the extraordinary becomes ordinary. Temporary measures settle in. Facilities meant to handle a surge become permanent fixtures. Budgets that were once justified as emergency spending turn into baselines. At that point, unwinding the system feels more dangerous than maintaining it, even to people who are uneasy about where it’s headed.

I’m not saying this trajectory is inevitable. I’m not saying it’s good or bad. I’m saying it’s familiar.

When America runs out of external wars, it doesn’t suddenly become peaceful. It looks inward, finds a problem big enough to absorb the machinery, and reframes that problem as a security necessity. That’s not ideology. That’s inertia.

Whether this continues, plateaus, or gets reversed depends on politics, economics, and events we haven’t seen yet. But the shape of it is visible now, if you’re willing to look at it as a system instead of a slogan.

That’s all this is meant to do.